I didn’t grow up as a fundamentalist, exactly, but I grew up in a context where a lot of fundamentalist ideas were considered normal.

My parents are charismatic evangelicals, in the special Anglican sense of the word that gave the world the Alpha Course. Most summers of my childhood included at least a week spent at the Royal Bath and West Showground, camping out with church-goers from around the UK who shared this approach to Christianity.

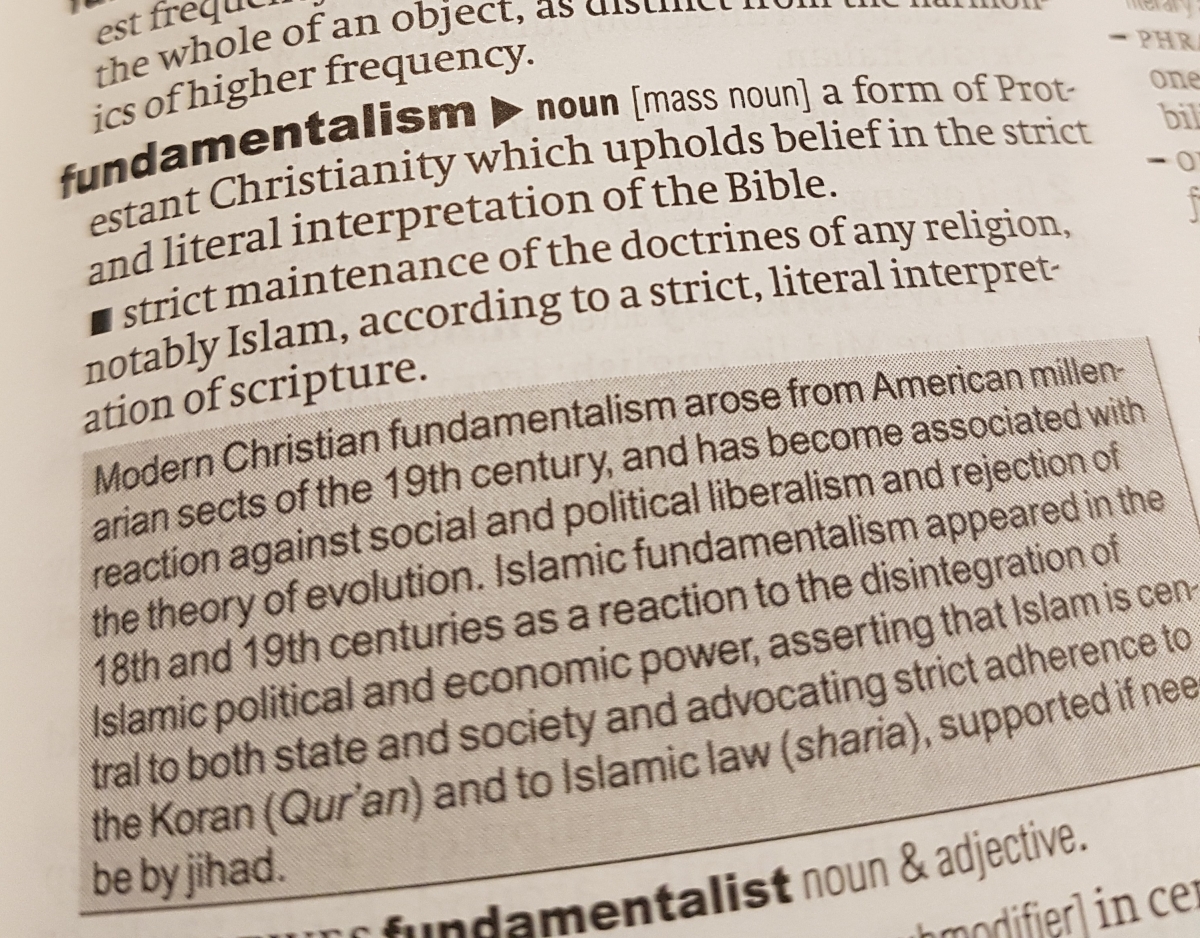

Image credit: Gary Dee via Wikipedia Commons

These days, I struggle to sit through modern worship sessions. They bring back bad memories. Memories of wanting to fit in, of wanting to believe, of desperately pleading with God to please, please, give me some kind of spiritual experience so that I’d know he was out there and that he cared about me. Memories of faking it, almost but not quite able to convince myself that this wave of warmth, this wobble in my legs, this garble coming out of my mouth was the real thing.

It never happened. Over time, trying to work out where I was going wrong, I read widely in the kinds of books that were recommended in our corner of Christian subculture. I read I Kissed Dating Goodbye (though nobody wanted to date me, so that seemed redundant). I read The Purpose-Driven Life, and many similar books on the boundaries of business management and life coaching. I read the life stories of persecuted modern Christians and tissue-thin theology by people like CS Lewis.

I really liked CS Lewis. If I haven’t read every published scrap he wrote, it’s not for lack of trying. Looking back, I think this might have been because Lewis was the least fundamentalist author I encountered. His apologetics might be crude and his vision occasionally distorted by misogyny or privilege in various ways, but he did have an inclusivity, a willingness to admit his own faults, and a general bonhomie that was in scarce supply elsewhere.

All of these ingredients came together to shape an understanding of the world that was starved for substance, brittle as spring ice, and comprehensive. I had found – had had to find – an answer for every question. Some of the answers weren’t very good, but that didn’t matter because there must be better answers out there.

I hoped to learn more. I was terrified to learn more. I was dimly aware that there were whole libraries of books out there that the little intellectual bubble I found myself in couldn’t even admit existed.

One of the dynamics of the Anglican-evangelical-charismatic convergence is that believing the Right Things is terribly important, having the right experiences is a sign that you’re okay, and that everyone is too nice to pry. As a result, a surprising range of views and perspectives gets pushed by a gentle but insistent social pressure into a generally accepted and acceptable format.

Preachers tread around a few favourite verses, or use different verses to express the same ideas again and again. There is a kind of safety in the self-reinforcing bubble. The potentially divisive topics are captured and quietly dispatched. Nobody says anything homophobic, but somehow gay church-goers don’t quite feel they can come out to their friends.

I went up to university longing for a broader world, and desperate to prove myself in the world I already knew. I was already afraid that those two desires were incompatible, and I didn’t know how to deal with the fear.

And, indeed, after about a year my careful faith-construction came tumbling down.